The hard truth: Finishing a book doesn't guarantee lasting understanding.

The solution: Structured processing after reading dramatically improves retention.

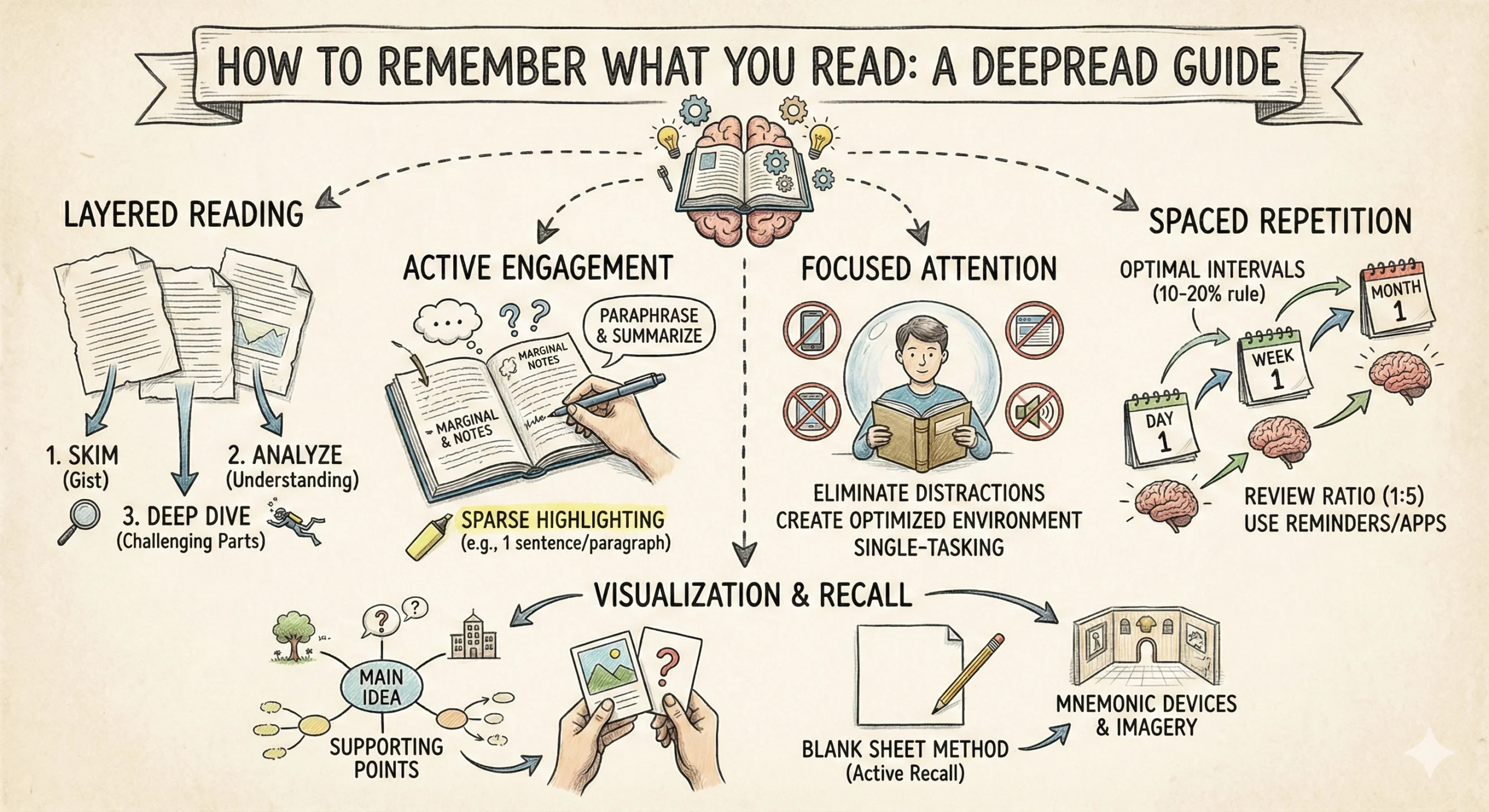

The formula: Reading + Externalized knowledge + Deliberate practice = Lasting understanding

Introduction: The Reading Retention Formula

Have you ever finished a book that absolutely blew your mind, only to find yourself struggling to explain its core message just a few weeks later? You're not alone.

Take a moment and think about the last book that fascinated you. Can you quickly summarize its main argument? What were the key ideas that resonated with you? Where exactly did it change your perspective, and why? What about that book you read a year ago?

If you're drawing blanks or fumbling for clear answers, you've encountered a universal challenge: simply reading a book doesn't guarantee you'll remember its insights when you need them most.

In this article, I'll show you that investing just a small amount of effort after finishing a book will dramatically improve your retention. The value you extract from reading will multiply exponentially when you dedicate even a fraction of your reading time to processing what you've consumed.

I'll introduce a technique for processing and applying what you read that automatically builds your external knowledge structure. This system grows more valuable with every book you read and process.

Best of all, this approach is completely scalable. You decide how much effort to invest after finishing a book—from a few minutes of basic organization to a deep exploration of the topic's nuances and connections.

Reading + Externalized knowledge + Deliberate practice = Lasting understanding

Finishing a Book Does Not Guarantee Lasting Understanding

After turning the final page of a book, we often experience an illusion of knowledge. We feel smarter, more informed, and eager to move on to the next title on our reading list.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: we've usually absorbed much less than we think. That warm glow of new understanding is deceptive. Without additional effort, much of what we've read will fade like a dream upon waking.

While it's certainly true that reading makes us smarter, transforming that temporary exposure into accessible knowledge requires intention. The insights you've gained need to be captured in a form you can revisit, integrate, and apply when needed in discussions, problem-solving, or creative work.

The techniques I'll share make it possible to transform a much higher percentage of what you read into lasting knowledge with minimal additional effort. And the structured approach ensures your time is well spent—you'll know exactly what to do next at each step, rather than aimlessly revisiting material.

Consider this: the time you'll spend processing what you've read is just a fraction of what you've already invested in reading and understanding the book. But this small investment delivers outsized returns.

Structured Processing After Reading Dramatically Improves Retention

Think of yourself as a mountain climber scaling a steep cliff. Each book you read represents an ascent to new heights of understanding. But without securing your progress, you risk losing what you've gained.

Experienced climbers place anchors (pitons) in the rock to secure their position before advancing. Similarly, readers need to solidify new knowledge before moving on to the next book.

This anchoring process serves several important functions:

- It prevents you from "falling" back to your starting point, losing the insights you worked to gain

- It makes it easier to revisit the material later, essentially creating a pre-established path

- It allows you to guide others through the same territory more effectively

- It provides a foundation for exploring related topics and alternative perspectives

The structured approach we'll discuss creates these knowledge anchors, turning the ephemeral experience of reading into durable understanding that remains accessible when you need it.

Externalized Knowledge and Deliberate Practice Are the Key to Long-Term Learning

To truly own what you've read, you need two key elements: externalized knowledge and deliberate practice.

Externalizing knowledge means extracting the implicit understanding you've gained from a book and making it explicit by writing it down. This could take the form of a summary essay, a nested bullet point list, a mind map, or a collection of note cards. The act of externalization forces you to clarify your thoughts and creates a permanent record you can revisit.

Deliberate practice means actively engaging with your new knowledge. Like a child with a new toy, you need to examine it from different angles, share it with others, combine it with existing knowledge, and even try to recreate it from memory. This active manipulation cements understanding in a way passive reading never can.

Together, these two approaches transform the temporary mental state created by reading into lasting intellectual capital you can draw upon indefinitely.

Externalized Knowledge: Creating Multi-Layered Learning Output

The most effective form of externalized knowledge is what I call a "multi-layered knowledge structure." This approach organizes information in hierarchical layers, making it easier to navigate, understand, and remember.

In the following sections, we'll explore what these structures are, how to build them, and which formats work best for different situations and learning styles.

What Is a Multi-Layered Knowledge Structure?

Returning to our mountain climbing analogy: a multi-layered knowledge structure is like establishing a series of base camps at different elevations. Each camp provides a stable platform from which you can launch further explorations or retreats.

These knowledge layers offer several advantages:

- They prevent complete knowledge loss if your memory fades

- They make it easier to revisit and reascend the mountain of understanding

- They allow you to guide others through the territory

- They facilitate exploration of alternative routes and perspectives

- They provide fallback points—you can always return to fundamentals if you get lost in complexity

At its core, a multi-layered knowledge structure organizes ideas hierarchically from general to specific. The top layer captures the broadest concepts and main arguments, while lower layers add progressively more detail, evidence, and personal connections.

One particularly effective approach is a question-based hierarchy, where each level is organized around key questions and their answers. This mirrors the natural way our minds process information and makes retrieval easier when we need it.

How Do You Build a Multi-Layered Knowledge Structure?

Fortunately, most well-written books already contain a useful structure you can leverage to build your multi-layered knowledge output. Start with the book's existing chapter organization, then identify points at three distinct levels:

First level: Main thesis, central questions, and core answers

This top layer captures the book's central argument—what problem is the author addressing, and what solution are they proposing? It's the "elevator pitch" version of the book that you could share in a brief conversation.

Second level: Supporting arguments and key concepts

This middle layer identifies the main components that build the thesis. What are the fundamental ideas and terms the author introduces? What major supporting arguments do they present? Think of these as the pillars supporting the main thesis.

Third level: Evidence and illustrations

This detailed layer includes personal experiences, observations, supporting evidence, examples, analogies, and detailed explanations. These are the vivid specifics that make the abstract concepts memorable and applicable.

By methodically working through the book and identifying elements at each of these levels, you create a comprehensive scaffold that preserves the book's knowledge in an accessible format.

Effective Formats of a Multi-Layered Knowledge Structure

Your externalized knowledge can take several forms, each with distinct advantages:

Summary essay with chapter structure

A traditional written summary following the book's organization provides a coherent narrative flow. This format excels at preserving context and showcasing relationships between ideas. It's particularly well-suited for books with a strong narrative arc or complex interconnected arguments.

Nested bullet point list

This format physically represents the hierarchical structure we've discussed, with indentation visually signaling the level of each point. It's excellent for quick reference and provides a clear overview of the book's structure. This approach works well for instructional or argument-driven nonfiction.

Hierarchical mind map

A spatial representation of the book's concepts creates a visual knowledge landscape. This format excels at showcasing relationships between ideas and can trigger spatial memory to aid recall. Mind maps work particularly well for complex concepts with many interconnections.

Slip box cards (Zettelkasten)

Individual note cards capturing single ideas (usually from the third level of your structure) create a modular knowledge system. This approach excels at facilitating connections between books and topics over time. The Zettelkasten method is particularly valuable for researchers and writers building a personal knowledge database across multiple sources.

Choose the format that best matches your learning style, the material at hand, and your intended use for the knowledge. Many readers find that combining approaches—perhaps a bullet-point summary plus a selection of Zettelkasten cards for key insights—yields the best results.

Deliberate Practice: Knowledge Retention and Application

Externalizing knowledge is only half the equation. To truly make what you've read your own, you need to actively engage with it through deliberate practice. Let's explore three increasingly powerful approaches to practice.

Revisiting Newly Acquired Knowledge

The simplest form of practice is revisiting what you've read. While rereading an entire book is rarely the most efficient approach (though some truly profound works may warrant it), there are more targeted ways to revisit content.

If you've highlighted key passages during your initial reading—whether on your Kindle or in a physical book—these can serve as concentrated distillations to review. However, this remains a relatively passive engagement with the material.

Your highlights become more valuable when you filter, prioritize, and categorize them. This organization makes them easier to search and revisit when you're engaging with similar topics in the future. Adding personal thoughts, analogies, or visual elements makes revisiting more engaging and productive.

This is where your multi-layered knowledge structure truly shines. It allows you to fluidly choose which level of abstraction to engage with during review—from broad concepts to specific examples. This flexibility transforms passive revisiting into active recreation of knowledge, which we'll explore next.

Recreating Newly Acquired Knowledge

To truly test and strengthen your understanding, challenge yourself to recreate what you've learned without directly referencing your notes or the original text.

The famous Feynman Technique exemplifies this approach: explain the concept as if you were teaching it to someone who knows nothing about the subject, using simple language and avoiding jargon. This forces you to translate complex ideas into your own words and reveals any gaps in your understanding.

Another powerful approach is question formulation and answering. Create questions that probe different aspects of the material, then attempt to answer them from memory. This mimics how you might apply the knowledge in real-world scenarios and strengthens retrieval pathways in your brain.

Your multi-layered knowledge structure facilitates this recreation process by providing checkpoints. You can start by trying to recall the book's main thesis and supporting arguments (levels one and two), then check your work against your notes. As your familiarity grows, challenge yourself to recall more specific details and examples (level three).

Developing Newly Acquired Knowledge

The highest form of practice involves not just remembering or recreating knowledge, but actively developing it—extending, critiquing, and integrating it with other ideas.

Dialectical note-taking involves organizing information as thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. For each major idea in a book, consider opposing viewpoints and how they might be reconciled. This process develops critical thinking and prevents uncritical acceptance of any single perspective.

Creating application scenarios bridges theory and practice. Ask yourself: "How could I apply this concept to my work, relationships, or personal projects?" Developing concrete use cases makes abstract knowledge tangible and memorable.

Linking ideas across different books and topics, as in the Zettelkasten method, creates a web of interconnected knowledge. When you connect a new concept to ideas you've encountered elsewhere, you strengthen your understanding of both and discover novel insights at their intersection.

Comparative analysis with related works—sometimes called syntopical reading—contextualizes the book within wider literature. How does this author's approach differ from others addressing the same topic? What unique contributions do they make? What blind spots might they have that others illuminate?

Engaging with a community around the material pushes your understanding to new levels. This could be as simple as responding to social media posts about the book, participating in forum discussions, or joining a book club. Articulating your thoughts to others and hearing their perspectives invariably deepens your own understanding.

For those without easy access to discussion partners, using AI chat tools can provide a flexible alternative. These tools can simulate discussion, ask probing questions, and adjust dynamically to your level of understanding—making them an on-demand practice partner available whenever you're ready to engage.

Conclusion: From Passive Reading to Active Knowledge Creation

Learning doesn't happen automatically. It requires effort—but not all effort is equally valuable. The approach I've outlined ensures you're investing your energy wisely, transforming reading from passive consumption into active knowledge creation.

By creating externalized knowledge structures and engaging in deliberate practice, you:

- Transform passive reading into a creative act that produces tangible intellectual assets

- Replace inefficient rereading with quick, high-powered revisiting of strategically organized material

- Progress from simply revisiting to actively recreating knowledge, strengthening neural pathways each time

- Build an external knowledge system that grows organically with each book you read, creating synergies between seemingly unrelated topics

This systematic approach to reading isn't just about remembering more—it's about thinking better. The externalized knowledge you create becomes a platform for new insights, connections, and ideas that wouldn't have emerged from reading alone.

Your Kindle highlights become launching points for deeper exploration. Book summaries evolve from static records to dynamic thinking tools. Your personal Zettelkasten grows into an intellectual partner that surprises you with connections you hadn't consciously made.

Start small. Apply these techniques to the next book you read. Create a basic multi-layered structure, engage in some simple practice exercises, and notice the difference in how much you retain and can apply weeks later.

Then watch as your external knowledge system grows, book by book, into a powerful resource that makes each new reading experience richer than the last. You're not just collecting books—you're building an intellectual ecosystem that evolves and enriches your thinking for years to come.

Remember: Reading + Externalized knowledge + Deliberate practice = Lasting understanding