Here's the pattern I've fallen into over the years: I hear about an interesting book, buy the audiobook for convenience, listen to it while commuting or exercising, and then feel this nagging sense that I should have absorbed more. The solution? Buy the Kindle version too. Read through it properly. Take highlights. Build my knowledge system.

This double-purchasing habit has become expensive and time-consuming. More frustrating, it suggests that my audiobook listening isn't actually effective learning—it's just entertainment with educational guilt attached.

When "Broken Money" landed on my radar, I decided to break this cycle. Instead of defaulting to my usual buy-both-versions approach, I would force myself to develop a system that extracts real knowledge from audio alone. The question wasn't whether audiobooks could be educational—it was whether I could make them educational for me.

Before diving into this audiobook experiment, let me explain what I'm trying to replace. My Kindle reading workflow has become pretty refined over the years:

I read with my finger constantly ready to highlight. When a passage strikes me as important, insightful, or connected to something I already know, I capture it immediately. After finishing each chapter, I review my highlights to ensure they represent the key concepts. Once I complete the book, I sync these highlights to DeepRead, where they're organized by chapter structure.

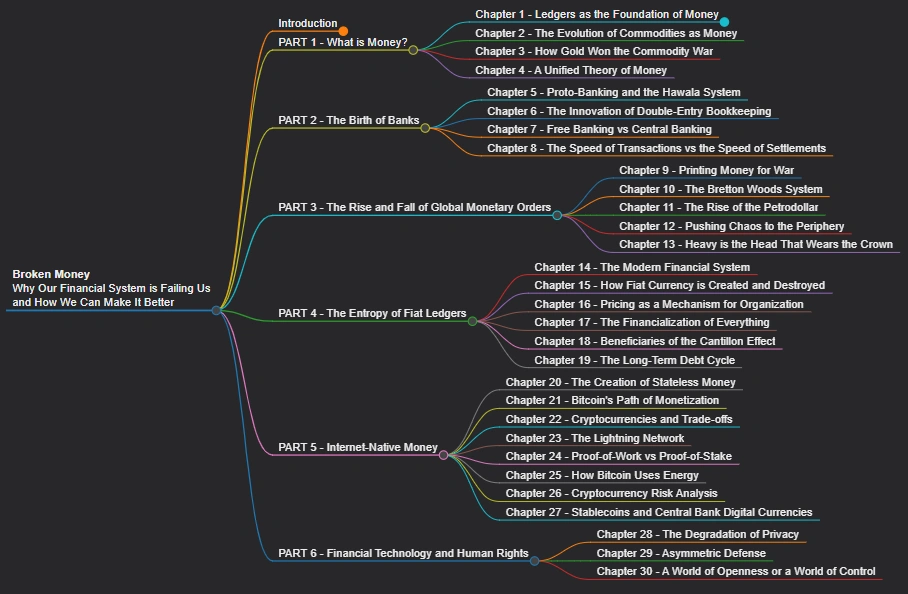

From there, I create mind maps that visualize the book's main arguments and supporting evidence. Finally, I extract keywords with explanations that become building blocks for future thinking and writing. These idea cards eventually connect with insights from other books, creating a web of knowledge that compounds over time.

This system works beautifully for text-based reading. It transforms passive consumption into active knowledge creation. But it completely breaks down with audiobooks, where highlighting is impossible and note-taking disrupts the flow of listening. That's exactly why I always ended up buying the ebook version anyway.

My audiobook consumption happens almost exclusively during bike rides—30 to 50-minute sessions where I'm moving through traffic, focusing on balance and navigation, with no ability to pause for notes. This creates a fundamental challenge: How do you capture and process information when your hands, eyes, and part of your attention are unavailable?

Traditional audiobook advice doesn't account for this reality. Most suggestions involve pausing frequently, taking immediate notes, or listening in stationary environments. But that defeats the main advantage of audiobooks: the ability to learn while doing other activities.

This constraint actually became the catalyst for my experiment. Instead of seeing my cycling listening time as a limitation, I decided to design a workflow that leveraged the unique aspects of this situation: extended, uninterrupted listening time combined with the mental space that comes from rhythmic physical activity.

Here's how the experiment is working so far. I listen to one chapter per ride, trying to absorb the main concepts without the pressure of immediate note-taking. During these 30-50 minute sessions, I focus entirely on understanding the flow of arguments and identifying key terms that seem central to the author's thesis.

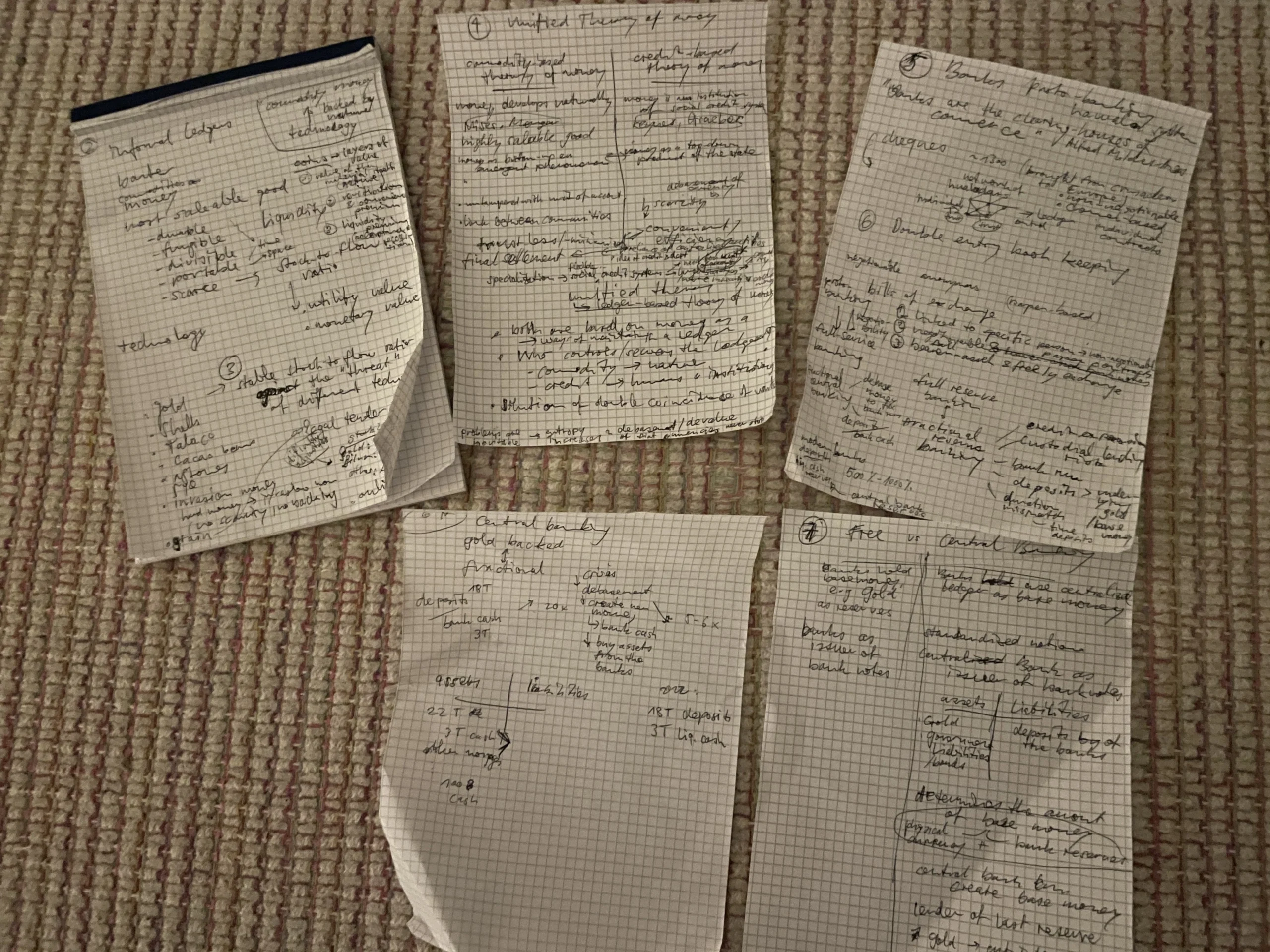

The magic happens immediately after I dismount. Whether I'm in my office changing room, at the calisthenics park, or back home, I grab whatever paper is available and frantically jot down everything I can remember. The notes look terrible—cramped handwriting on scraps of paper, keywords scattered without obvious organization, chapter numbers scribbled in margins. But they capture the essential elements before they fade from short-term memory.

My Paper-Scribbling Process:

Chapter number at the top, then a rapid brain dump of every key term, concept, or insight I can recall. No structure, no elegance—just capture everything before it disappears. Names, numbers, frameworks, examples—anything that felt important gets written down.

At the end of each week, I collect these messy paper scraps and begin the real work: organizing them into a coherent knowledge graph. I type up the keywords chapter by chapter, then ask an AI assistant to review my list and identify any major concepts I might have missed. This conversation often reveals gaps in my understanding or helps me clarify concepts I only partially grasped.

Once I'm confident in my keyword list, I ask the AI to provide explanations, examples, or additional context for each term. This step transforms my raw notes into a structured reference document. For "Broken Money," I'm building this knowledge graph progressively, with each chapter adding new concepts while connecting to previously established ideas.

The entire process feels experimental and slightly chaotic. But that's exactly what makes it interesting. I'm discovering which types of information stick naturally from audio consumption and which require additional processing. Some concepts—especially those tied to stories or examples—embed themselves naturally. Others—particularly technical definitions or numerical data—need more deliberate capture and reinforcement.

After a week of testing this approach, I'm surprised by what's working. The constraint of delayed note-taking actually forces me to listen more actively during the bike rides. I find myself paying closer attention to the structure of arguments, anticipating which concepts will be important enough to remember, and mentally rehearsing key terms.

The physical activity seems to enhance rather than distract from comprehension. There's something about the rhythm of cycling that creates mental space for processing complex ideas. I often find myself understanding connections between concepts during these rides that I might have missed while sitting stationary.

However, the paper-scribbling phase remains problematic. The time pressure and uncomfortable writing conditions lead to incomplete captures and illegible notes. Sometimes I can't read my own handwriting when I return to organize the information later in the week.

The bigger question remains unanswered: Am I actually learning as much as I would through my traditional Kindle workflow? I won't know until I complete the entire book and test my retention over time. But early signs are promising. When I review my "Broken Money" knowledge graph, I can recall not just the concepts themselves but the context in which I learned them—the particular bike ride, the weather conditions, the moment of understanding that emerged while pedaling.

This contextual embedding might actually strengthen long-term retention compared to static text highlighting. We'll see if that hypothesis holds up when I try to access this knowledge in conversations or writing months from now.

The experiment continues. I'm committed to seeing it through to completion, documenting what works and what doesn't, and sharing the full results. Whether this approach succeeds or fails, I'm learning something valuable about the relationship between attention, constraint, and knowledge acquisition. Sometimes the most effective learning systems emerge from embracing limitations rather than trying to eliminate them.

Stay tuned to find out whether I finally break my buy-both-versions habit, or whether I end up sheepishly purchasing the Kindle edition of "Broken Money" after all.