In my previous articles, I explored what you could do with AI that has access to your book highlights — building mind maps, generating flashcards, challenging arguments, capturing insights. Then I described the vision of cross-library AI workflows that synthesize knowledge across your entire reading history.

Now comes the harder question: How do you actually make this work?

The challenge is retrieval. Your highlights are scattered across dozens or hundreds of books. Some books you highlighted heavily — capturing the complete argument. Others you highlighted selectively — just a few passages that struck you. The insight you need might be a full chapter in one book, a passing remark in another, or buried in a fictional character's monologue in a novel you read years ago.

How do you help an LLM find the right insight at the right time? How do you set up a system so that when you ask about "free will," it surfaces not just the obvious philosophy books, but also that German-language Dostoevsky passage where a character wrestles with determinism — even though the words "free will" appear nowhere in the text?

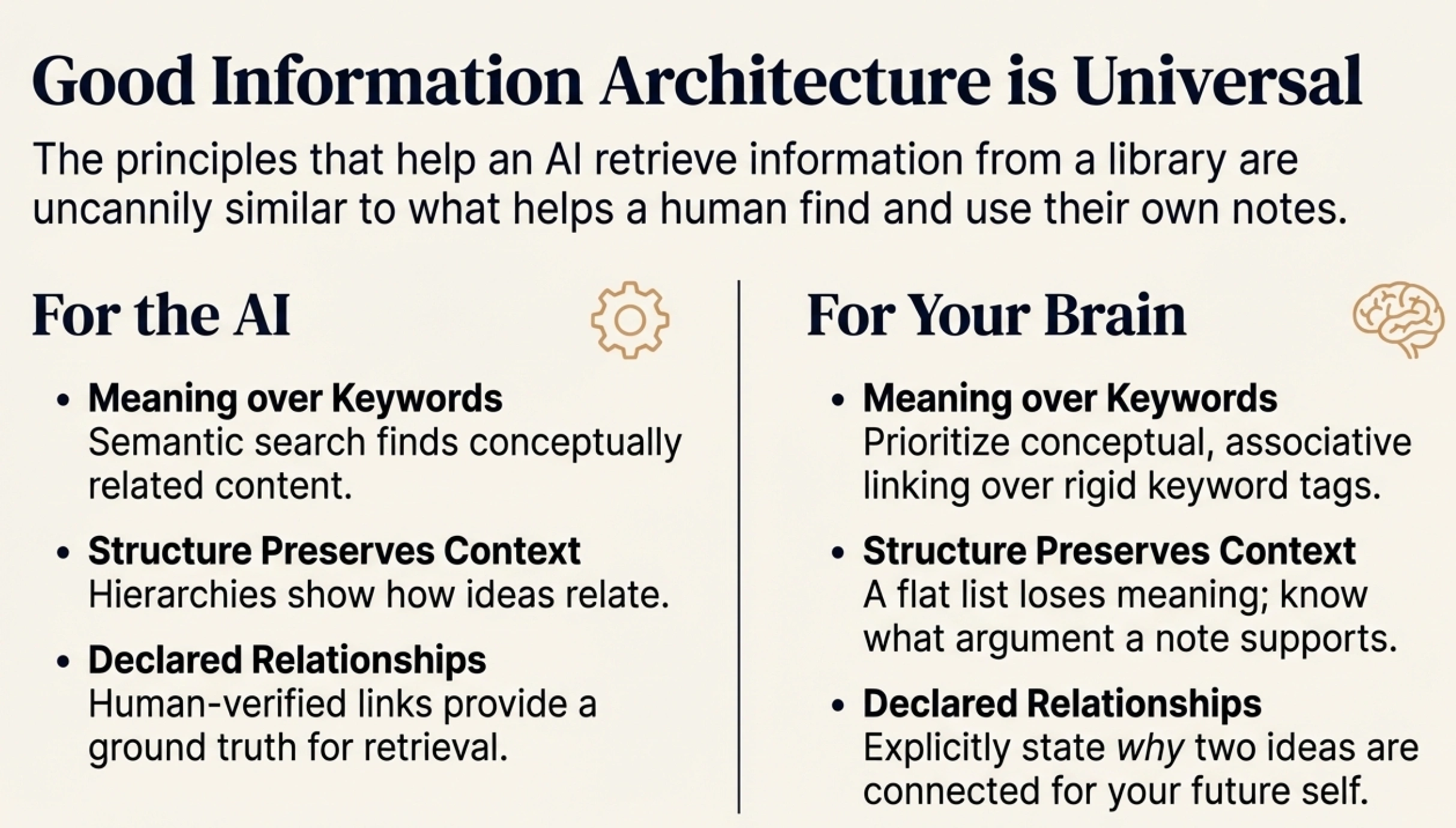

This is what I'm experimenting with. And as I work through the technical challenges, I keep noticing something interesting: the principles that help an LLM retrieve information seem oddly similar to what helps human notetakers find their own notes. I'm not sure yet if this parallel is deep or superficial, but I'll share these observations as we go.

This article isn't just for technical readers. If you've ever struggled to find something you know you wrote down somewhere, or wondered how to structure your notes so you'll actually stumble across them when you need them, the underlying questions are the same.

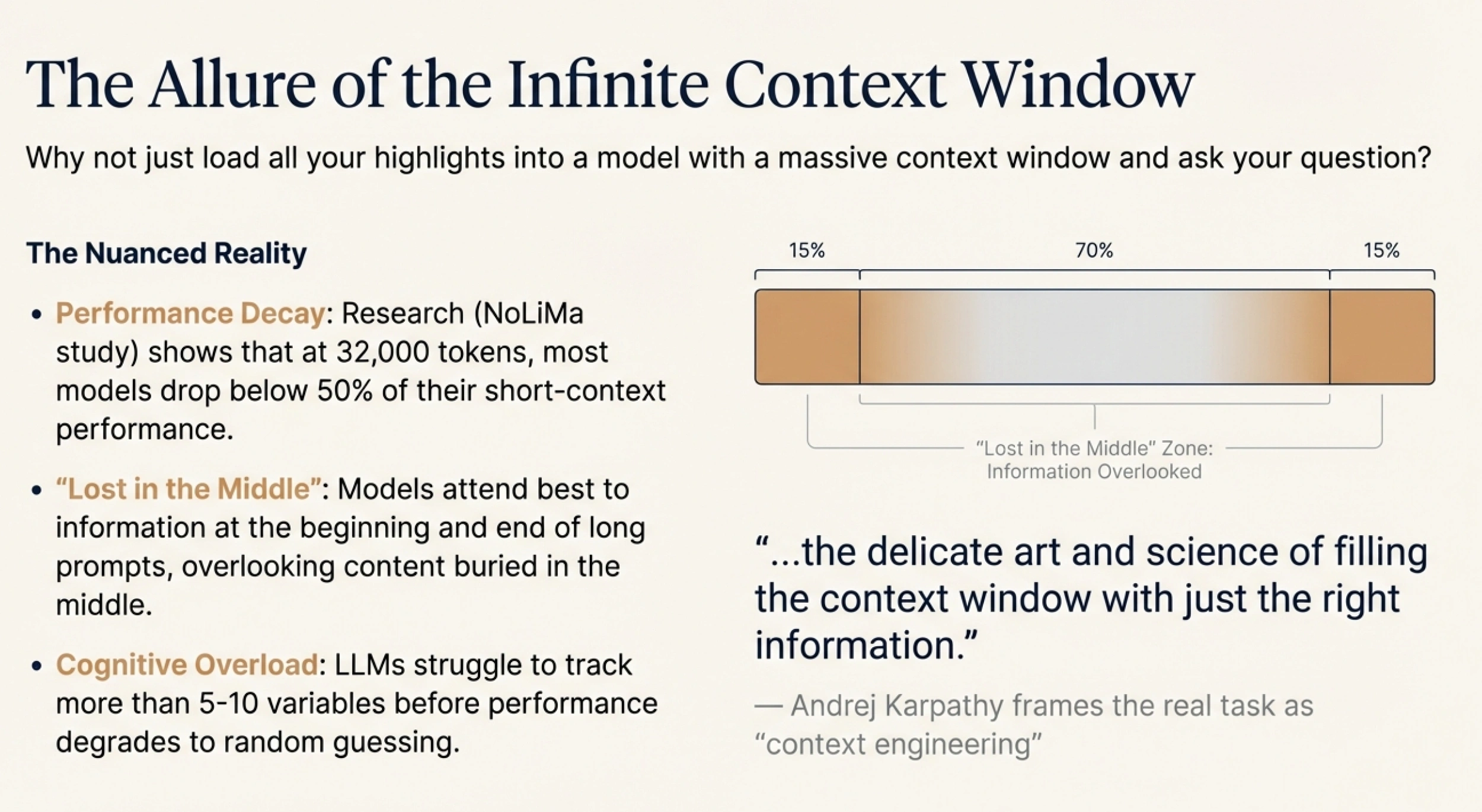

The obvious objection to everything I'm building is simple: why not just use a model with a massive context window? Load all your highlights at once, ask your question, done.

Context windows have grown dramatically. Some models now handle hundreds of thousands or even millions of tokens. That's enough to load many books' worth of highlights in a single prompt. Problem solved?

Not quite.

Research tells a more nuanced story. A study called NoLiMa found that at 32,000 tokens, 11 out of 12 tested models dropped below 50% of their short-context performance. Another experiment showed that LLMs can reliably track only 5-10 variables before degrading to random guessing. There's also the well-documented "lost in the middle" problem — models tend to attend better to information at the beginning and end of long prompts, while content buried in the middle gets overlooked.

Andrej Karpathy, the AI researcher, frames this well. He talks about "context engineering" as "the delicate art and science of filling the context window with just the right information for the next step." The key phrase is "just the right information." A bigger context window doesn't help if it's filled with irrelevant content. In fact, it might hurt — the signal gets lost in the noise.

Think of it like an autistic savant who can recall extraordinary detail from memory — the exact score of a soccer match from twenty years ago, every word on a page they glanced at once. Perfect recall. But synthesis is different. Knowing everything doesn't mean you can pull together the relevant pieces to answer a novel question.

There's also a practical problem specific to book highlights: uneven density. Some books in my collection have hundreds of highlights — I captured the complete storyline. Others have just a handful — only the moments that truly struck me. If I dump everything into a big context window, the heavily-highlighted books dominate. A profound insight from a sparsely-highlighted book might never surface because there's simply less text from that book competing for the model's attention.

The deeper issue is this: the LLM needs structure, not just data. It needs to understand what kind of information it's looking at. Is this a main argument or a supporting example? Is this the author's own view or an objection they're addressing? Is this from the introduction or the conclusion?

A raw dump of highlights throws all of this away.

So if loading everything isn't the answer, what is? I've been exploring several approaches, each with different strengths. What I'm finding is that they're not mutually exclusive — the best system probably combines them.

The foundation of my current setup is semantic search. Instead of matching exact keywords, semantic search uses embeddings — numerical representations of meaning — to find content that's conceptually related to your query.

Here's how it works: each chunk of text (a highlight, a note, a summary) gets converted into a vector of numbers using an embedding model. When you search, your query gets converted the same way. Then the system finds chunks whose vectors are mathematically similar to your query vector — regardless of whether they share any words.

This is powerful. When I search my library for "free will," the system doesn't just find highlights containing those exact words. It finds passages about choice, determinism, agency, moral responsibility — anything semantically related.

The most striking example: I've read several Dostoevsky novels in German. They contain profound passages wrestling with questions of free will and human agency. When I search in English for "free will," the system surfaces these German-language quotes — even though they contain none of the English keywords I searched for. The embedding model understands that these passages are conceptually relevant.

My setup uses OpenAI's text-embedding-3-small model to generate embeddings, stored in a SQLite database. Search works by computing cosine similarity between the query embedding and all stored embeddings, then returning the highest-scoring results.

A note for notetakers: This is why tagging systems based purely on keywords feel limiting. You tag a note "productivity" but later search for "getting things done" and don't find it. Semantic organization — grouping by meaning, not just words — is more robust. Whether you're organizing for an AI or for your future self, the principle is the same.

I spent time studying GraphRAG, a more sophisticated approach developed by Microsoft that builds knowledge graphs from documents. I won't be implementing it — the computational cost is too high for my use case — but I learned something important from it.

In one example from a GraphRAG presentation, they discuss a legal document. The document has a main section stating various rules, and then a later chapter titled "Exceptions." If you chunk the document algorithmically — splitting it into pieces based on token count — an AI might retrieve a rule from the main section without the relevant exception. It would give you a confidently wrong answer.

The problem is that the AI doesn't understand the document's structure. It doesn't know that the "Exceptions" chapter modifies everything that came before. It's just matching text to queries, blind to how the pieces fit together.

Books work the same way. A highlight from Chapter 1 might introduce a concept that gets completely reframed by Chapter 10. An author might present an objection in one section and refute it three chapters later. If your retrieval system doesn't preserve this structure, it can surface misleading fragments.

This is where DeepRead's exports become valuable. When you export highlights from DeepRead, they come with the chapter structure intact — highlights nested within their chapters and sections. Most other highlight export tools give you a flat list. DeepRead preserves the hierarchy, which turns out to be essential for teaching an AI how the book is organized.

A note for notetakers: This is also why dumping notes into a single folder often fails you later. You lose the context of when and why you wrote something, what it connected to, where it fits in a larger argument. The same principle that helps AI understand your notes helps you understand them too.

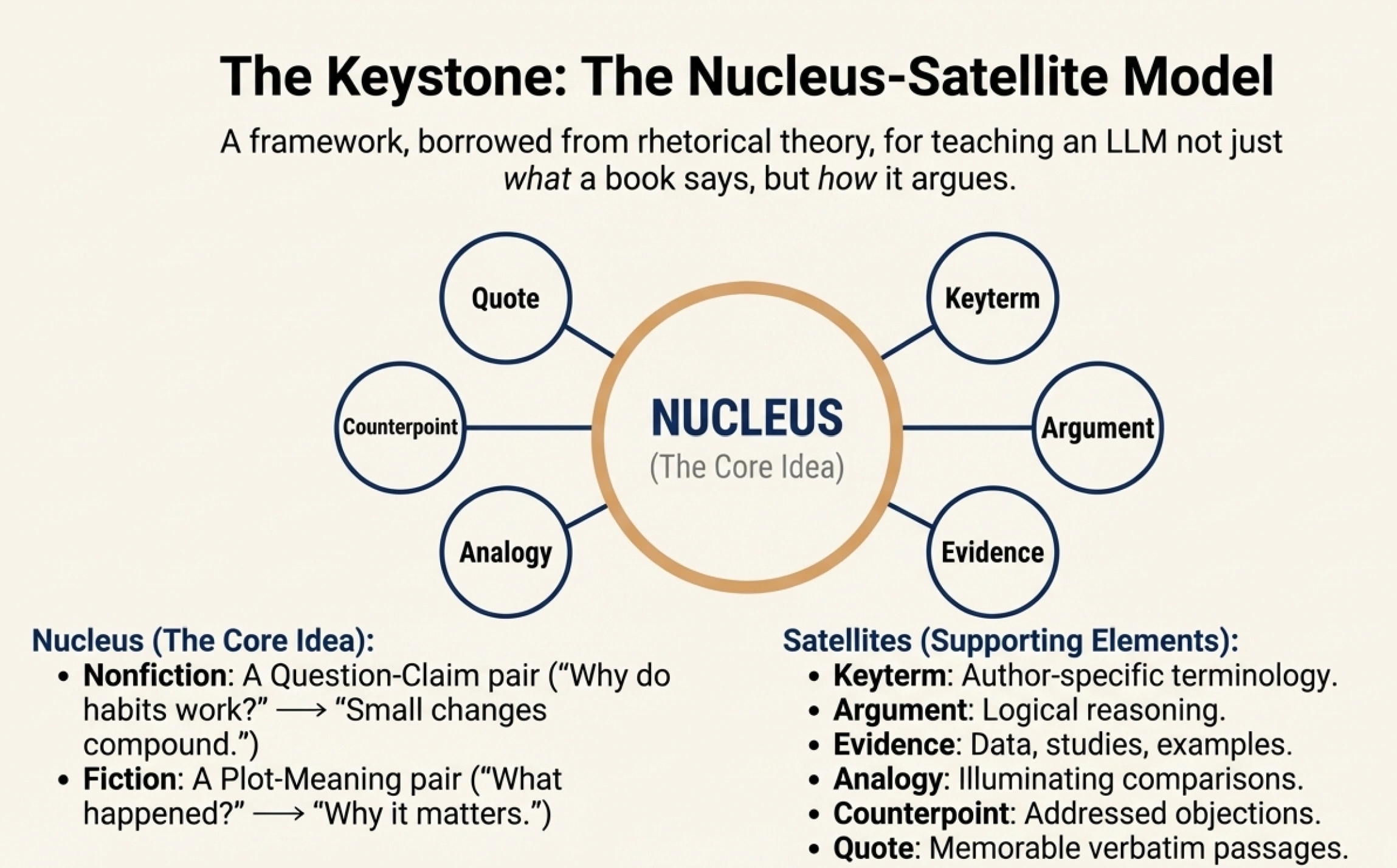

The most novel part of my setup is what I call "structural indexing" — teaching the LLM not just what the book says, but how it argues.

At the heart of this is the nucleus-satellite model, borrowed from rhetorical theory. Here's the idea:

A nucleus is the core idea unit. For nonfiction, it's a question-claim pair: "Why do habits work?" → "Small changes compound over time." For fiction, it's a plot-meaning pair: "What happened?" → "Why it matters."

Satellites are the supporting elements that orbit each nucleus:

When I process a book through my system, Claude reads through the highlights chapter by chapter — the same way a human would read a book — and identifies these structural elements. It proposes which highlights are nuclei (main arguments), which are satellites (supporting evidence), and how they relate to each other. Then I confirm or adjust this structure.

This is where human intelligence enters the pipeline. The relationships are declared, not guessed. When a quote is marked as supporting a specific claim, that's a fact I've verified — not a probabilistic inference the system made on its own.

The result is that when I later search for something, the system knows not just that a passage is relevant, but what role it plays. Is this the author's main claim or just an example? Is it a definition I should trust or an objection they're going to refute? This context makes the search results far more useful.

A note for notetakers: The nucleus-satellite model wasn't invented for AI — it comes from rhetorical structure theory, developed to understand how humans organize arguments. The fact that it helps AI navigate books suggests something interesting: good structure is good structure, whether the reader is human or machine. If you're struggling to organize your own notes, try asking: What's the main claim here? What supports it? You might find this framework helpful for your own thinking.

Different queries need different strategies. If I'm searching for a specific term an author uses, keyword matching might be fastest. If I'm exploring a concept, semantic search finds related ideas even when the words differ. If I want to understand an author's argument, the structural information tells me which pieces are central versus peripheral.

The system I'm building can route queries to different approaches — or combine them. Search for "compound interest" might find exact matches first, then expand to semantically similar concepts, all while using structural metadata to prioritize main arguments over passing examples.

One area I haven't implemented yet is LlamaIndex, a framework that enables hybrid search (combining semantic and keyword approaches), agent-based retrieval (where the AI decides which sources to query), and multi-step reasoning (breaking complex questions into sub-questions). Based on the promising results I'm already seeing, I expect adding LlamaIndex will significantly improve retrieval quality.

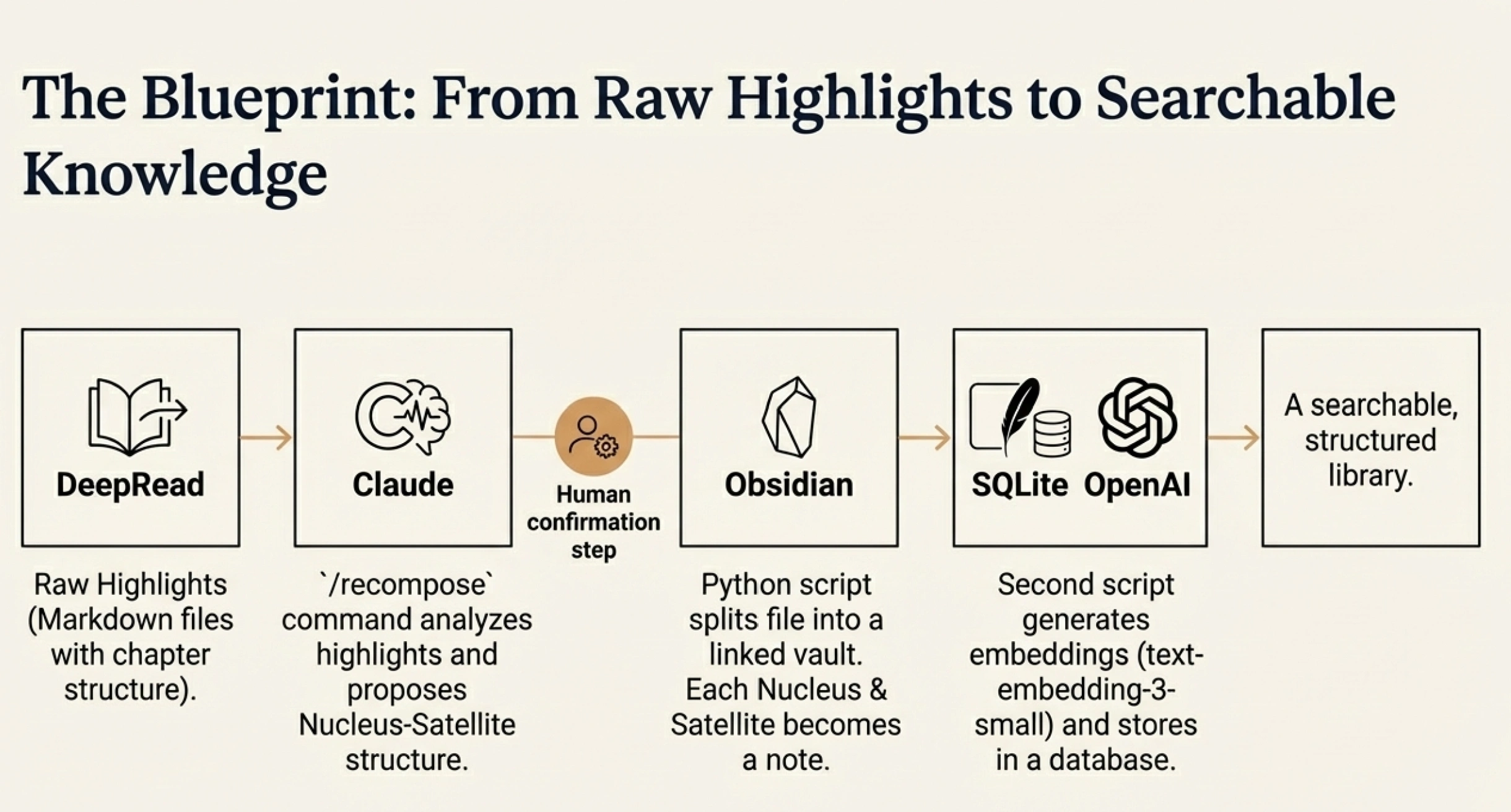

Let me walk you through the actual pipeline I've built.

It starts with raw highlights exported from DeepRead. These come as markdown files with the chapter structure intact — each highlight nested under its chapter heading. This is the raw material.

Next comes what I call the "recompose" step. I run a command in Claude Code (/recompose book_slug) and Claude analyzes the highlights. It proposes a nucleus-satellite structure for the book: which highlights represent main arguments, which are supporting evidence, how they relate to each other. Crucially, Claude waits for my confirmation before proceeding. This human-in-the-loop step is where I verify that the structure makes sense.

The output is a single nested file — a structured representation of the entire book with all the metadata: book-level thesis, chapter summaries, nuclei with their question-claim pairs, satellites categorized by type, and original highlights linked to the elements they support.

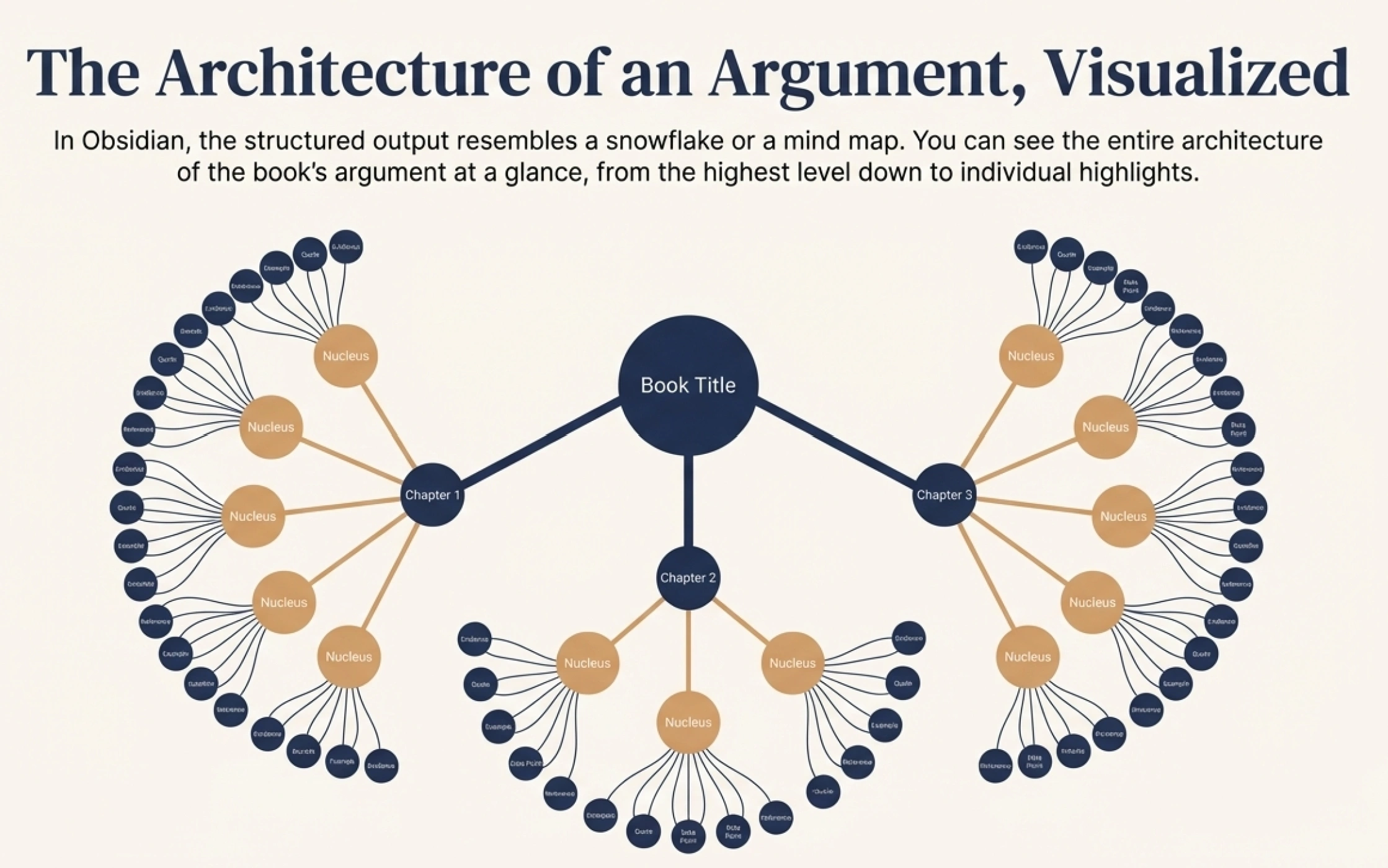

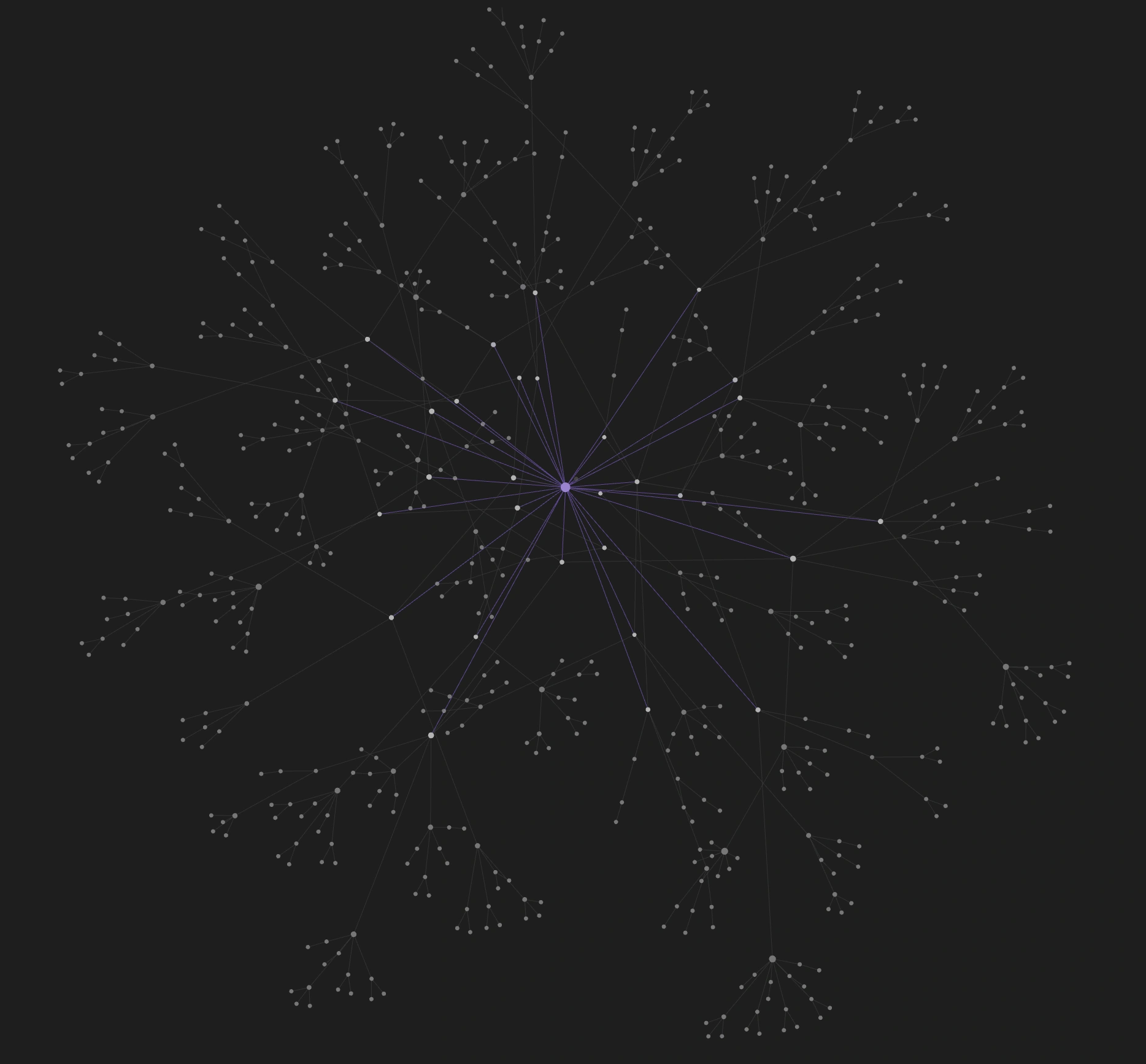

Then a Python script splits this nested file into an Obsidian-compatible vault. Each nucleus becomes its own file. Each satellite becomes its own file. They're all linked together through parent-child relationships. The result is a knowledge graph you can explore visually.

In Obsidian, this looks like a snowflake. The book sits at the center. Parts branch out from it. Chapters branch from parts. Nuclei branch from chapters. Satellites branch from nuclei. Highlights connect to their satellites. You can see the entire architecture of the book's argument at a glance.

Finally, another Python script indexes everything. It scans all the markdown files, generates embeddings for each piece, and stores them in a SQLite database. Now the book is searchable — semantically and structurally.

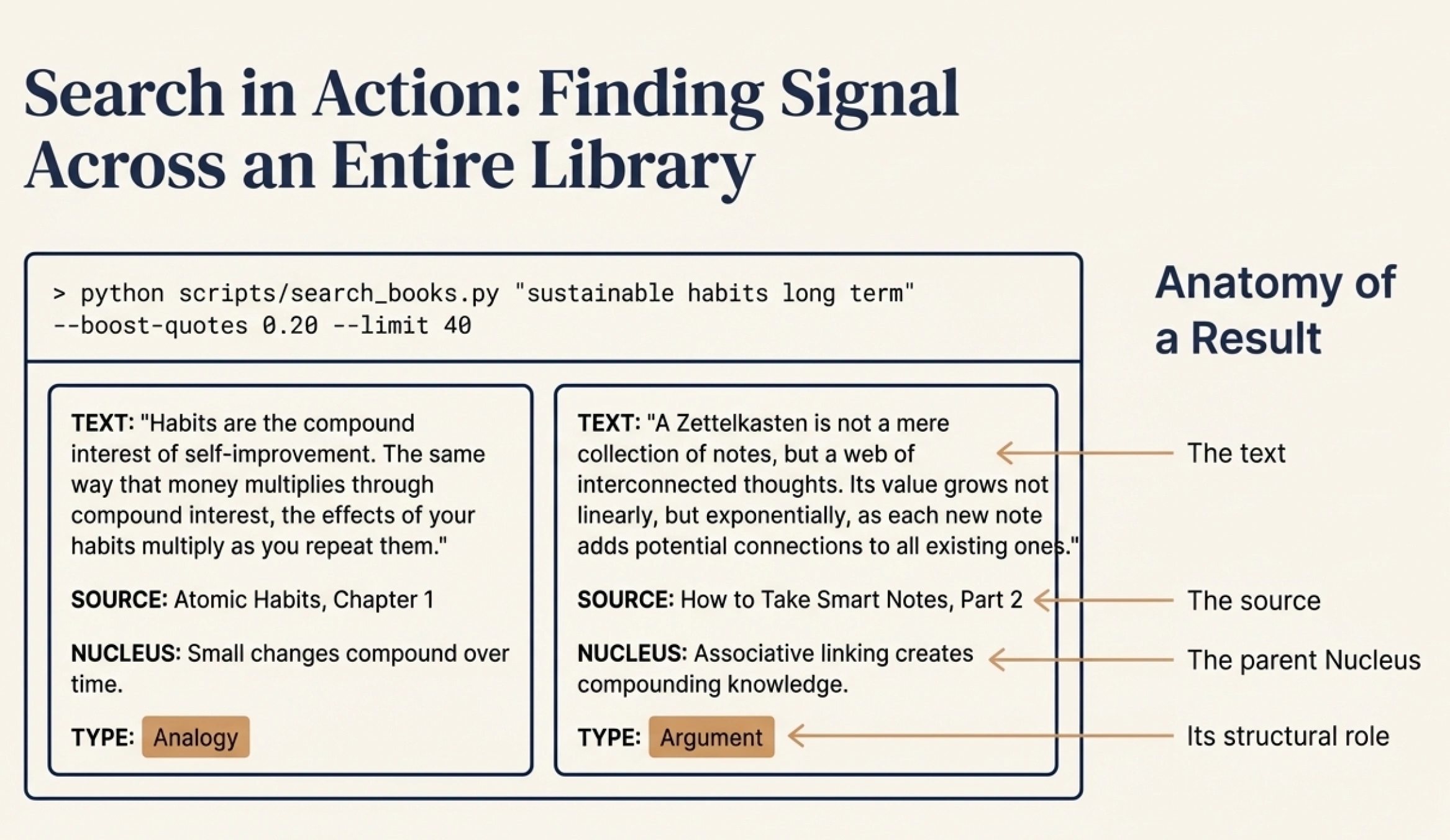

Once multiple books are indexed, I can search across my entire library:

python scripts/search_books.py "sustainable habits long term" --boost-quotes 0.20 --limit 40

The system finds relevant passages across all indexed books, ranks them by semantic similarity, and outputs the results to a markdown file. I can filter by book, by structural level (show me only nuclei, not supporting evidence), or by satellite type (show me only the key terms). I can boost certain types — giving quotes slightly higher priority, for example.

The search results include context: which chapter each passage comes from, what the parent nucleus is, whether this is a main argument or supporting evidence. This makes it much easier to evaluate whether a result is actually what I'm looking for.

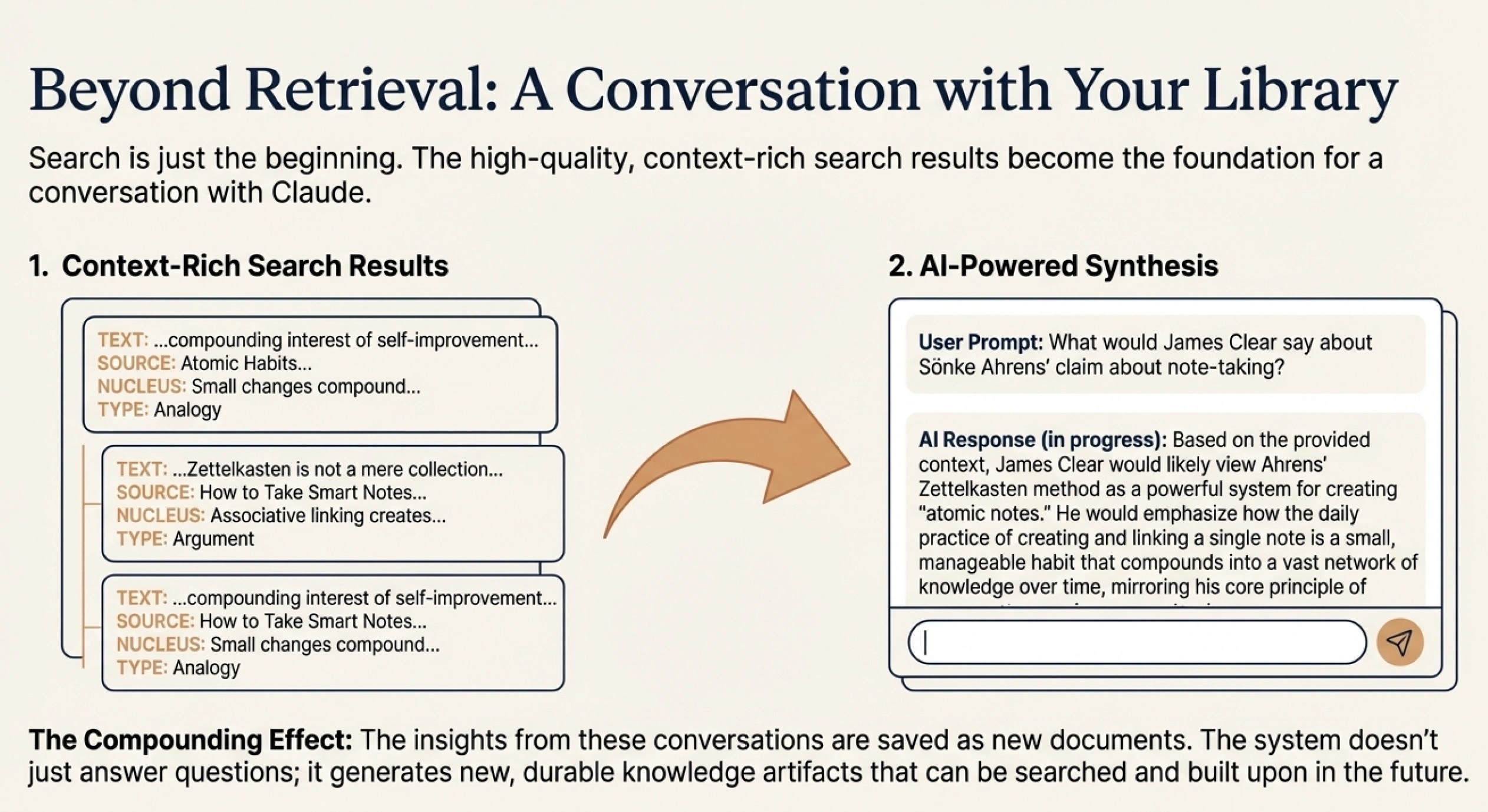

Search is just the beginning. Once I have relevant passages, I can have a conversation with Claude about them:

The insights from these conversations get saved to an analyses folder. Each interaction creates something tangible — not just a chat that disappears, but a document I can return to, search through, and build upon.

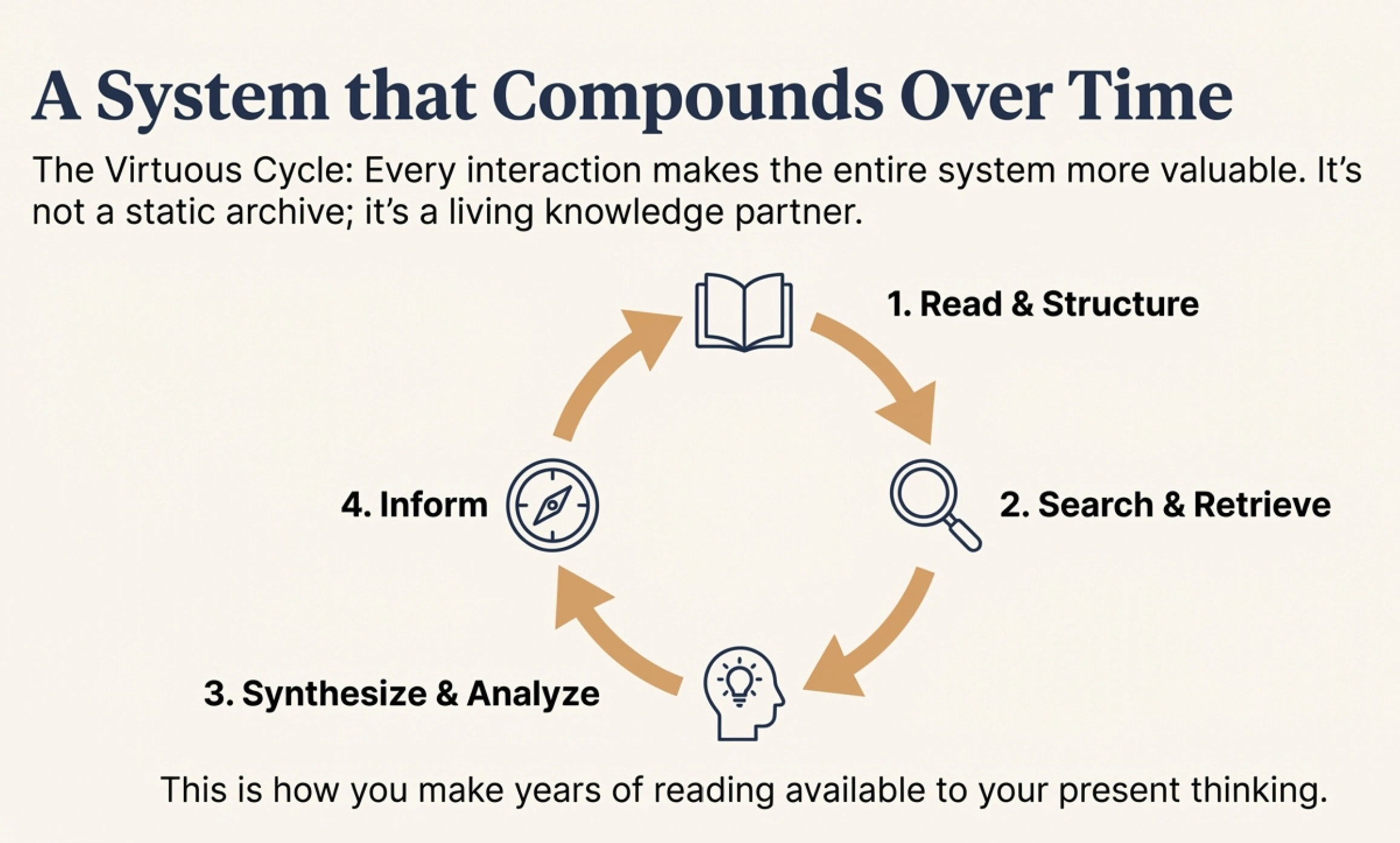

This is what I mean by the system compounding over time. New books expand the knowledge base. Searches reveal cross-book patterns. Analyses create synthesized insights. Those insights inform future reading choices. Every interaction makes the whole system more valuable.

I haven't finished building everything I've described — LlamaIndex integration is still on the roadmap, and there are features I want to add. But even the current setup has produced results that surprised me.

The Dostoevsky example I mentioned earlier — finding German-language quotes on free will from an English query — was a genuine "this actually works" moment. The system found conceptually relevant content across language barriers, without any special configuration for multilingual search.

I've also had moments where the search surfaced a highlight I'd completely forgotten, from a book I read years ago, that turned out to be exactly what I needed for something I was working on. This is what I was hoping to build: a system that makes your past reading available to your present thinking.

Throughout this article, I've been sprinkling observations about how the principles that help AI might also help human notetakers. Let me gather those threads.

The core challenge is the same: you have a large body of information, and you need the right piece to surface at the right time. Whether you're designing for an AI or for your future self, you're asking the same question: how do I structure this so the relevant thing can be found?

Some patterns that emerged:

Meaning over keywords. Semantic organization — grouping by concept rather than exact words — is more robust than tag-based systems. This is why linked notes (Zettelkasten, Obsidian) often work better than folder hierarchies. The same principle that makes semantic search powerful for AI makes associative linking powerful for humans.

Structure preserves context. Flat lists lose information. When you know where something fits — what argument it supports, what question it answers, whether it's a main point or a supporting example — retrieval becomes much more useful. This is true whether the retriever is an algorithm or your own memory.

Declared relationships beat inferred ones. When I manually confirm that a quote supports a specific claim, that relationship is solid. It's not a guess the system made. The same principle applies to human note-taking: explicitly linking ideas ("this connects to X because...") creates stronger retrieval paths than hoping you'll remember the connection later.

The middle path. My system sits between fully manual note-taking (accurate but labor-intensive) and fully automated RAG (scalable but lossy). The insight is that human intelligence is most valuable at the structuring phase — deciding what the main arguments are, how pieces relate — while AI can handle the tedious work of indexing and retrieval. This division of labor might apply to personal note systems too: spend your energy on understanding and organizing, let tools handle storage and search.

I'm not claiming these parallels are fully developed. This is speculation, not a thesis. But I find it interesting that teaching an AI to navigate knowledge seems to surface principles that might help humans navigate their own notes. Maybe good information architecture is good information architecture, regardless of who's doing the reading.

This is an ongoing experiment, not a finished product. I'm documenting what I'm learning as I build it.

Eventually, we plan to bring these capabilities into DeepRead directly — so users can benefit from cross-library AI without setting up their own technical infrastructure. But we're not there yet, and I don't want to promise features we haven't built. Right now, this is about exploration and learning.

If you're interested in experimenting with this yourself, here are some paths:

Join the co-development community. We're looking for a small group of dedicated readers to test features and share feedback as we build. Your use cases will directly shape what we prioritize. You can learn more at deepread.com/pro-ai-features.

Experiment on your own. If you're technical and want to try this, you can export your highlights from DeepRead — they'll come with chapter structure intact as markdown files. From there, you can write prompts to restructure them into a nucleus-satellite format and experiment with Claude Code to search and analyze them. If you go this route, I'd love to hear what you learn.

Share your learnings. Whether you're building something similar or just thinking about these problems, I'm interested in hearing from you. What workflows would be most valuable? What did you try that worked or didn't work?

Get the prompts. I'm considering creating a video walkthrough of the complete setup. If you want access to the specific prompts I'm using, or want to discuss the technical details, reach out directly.

Contact me at [email protected]. I'm genuinely interested in building this together with readers who care about making their reading more useful.

The effort to structure your highlights is real. But so is the payoff: a system that makes years of reading available to your thinking, exactly when you need it.

Ready to shape the future of DeepRead? Join the co-development community.

What you get:

Your committment: