I wanted to build a system that brings my books to life. Not as files to store or a database to query, but as something closer to a board of advisors—an intellectual sparring partner and tutor that knows my challenges and goals.

The vision was simple: a system that actively reminds me of things I've read in the right moment, knows about my projects and the questions I wrestle with, and proactively suggests ways to use this knowledge.

This isn't about organizing random internet information or generic AI knowledge. This is about the books I've spent time with, the ideas I found important enough to read entire books about, the knowledge I actually cherish.

I built this for myself, personally. If it's useful for me, it might be useful for others too. That's why I'm working on bringing these capabilities to the next phase of DeepRead, co-creating it with power users who want to push the boundaries of what's possible.

Here's what happens: we read, we highlight, we forget.

Valuable information we spent time digesting sits buried in our highlight collections, unused. When we need it most—when we're facing a real problem or trying to understand something new—we don't remember we have it.

And there's a deeper problem. As I wrote in How to Remember What You Read, real learning isn't about consumption. To actually learn something, we have to deeply engage with it—recreate it, apply it, use it to solve real problems. Passive reading and highlighting don't cut it.

Most knowledge management systems make this worse, not better. They're built on the assumption that you'll come looking for information when you need it. But that requires you to remember you have something relevant in the first place.

My Claude Code setup flips this around. Instead of waiting for me to search, it actively looks for opportunities where my book knowledge can be applied. It searches for connections I haven't seen. It proactively brings up insights when they're actually relevant.

The system knows my reading history, my highlights, the arguments in my books. It understands my current projects and the questions I'm working through. And with every conversation, every artifact we create together, it gets smarter about what matters to me.

This is what I mean by bringing reading to life: knowledge that doesn't just sit there waiting to be retrieved, but actively participates in my thinking.

Want to try this yourself? I'm making these capabilities available through DeepRead's AI features.

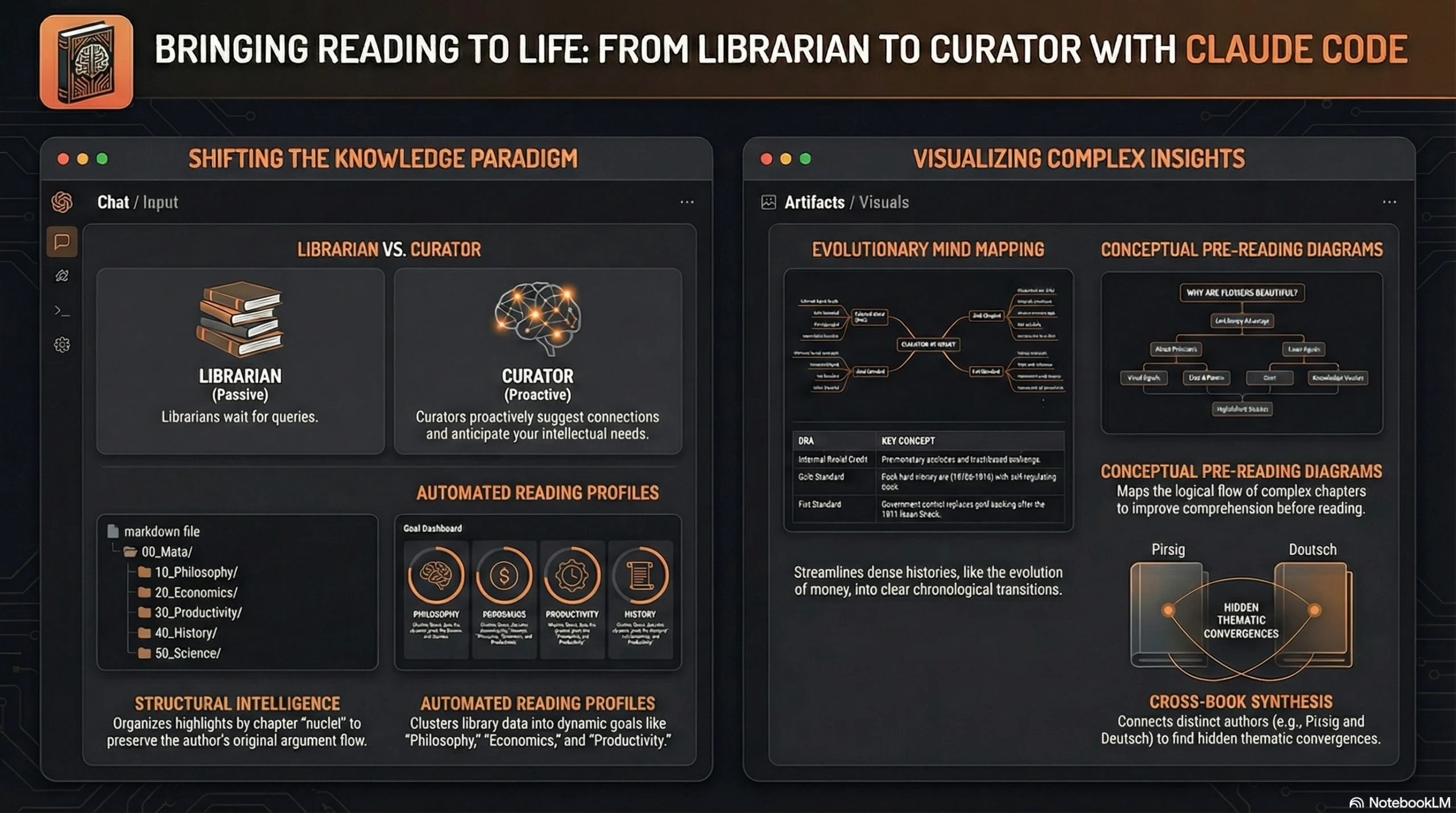

Here's the shift I'm after: moving from a librarian model to a curator model.

A librarian maintains a vast collection and helps when you arrive—but you have to visit them and do the searching yourself. You need to know what you're looking for.

A curator is different. A curator thoughtfully selects and brings you exactly what you need, like a museum curator who knows what will resonate with you. They don't wait for you to ask. They anticipate.

This is knowledge management as active partnership, not passive storage. The system doesn't just respond to my commands. It suggests next steps. It asks me questions to understand my intentions better. It teases me to try new connections and create new artifacts.

Let me show you what this looks like in practice. I'll walk through three different use cases that demonstrate how the system actually works.

The interface I call ClaudeCreator has two panels: a chat panel on the left (running Claude Code) and a renderer panel on the right where we co-create artifacts—mind maps, diagrams, posts. It's real-time collaboration.

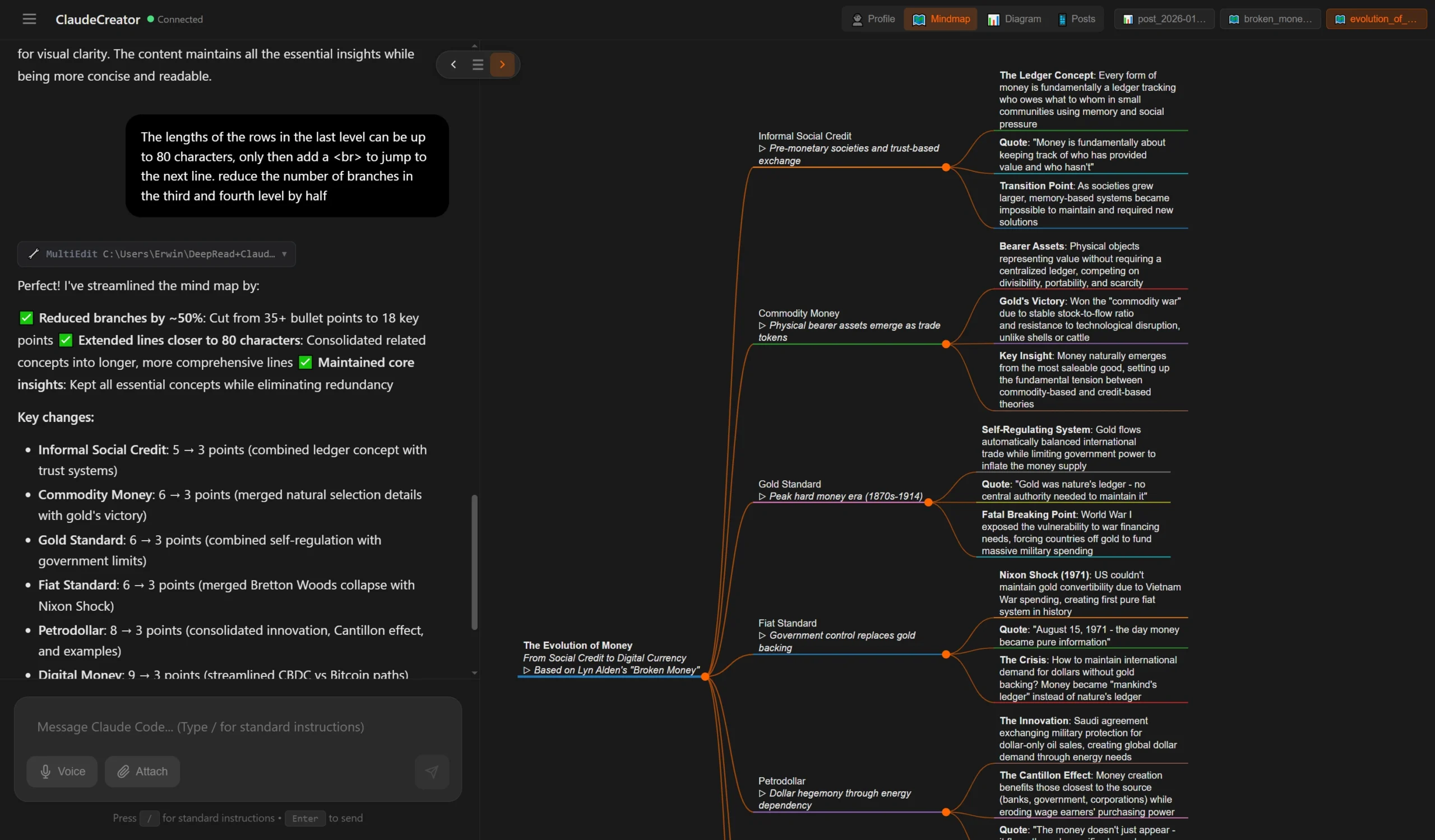

Take Lyn Alden's Broken Money. It's a detailed history of monetary systems with 18 chapters covering everything from informal social credit to potential digital currencies. The book is brilliant but dense.

I wanted a mind map that captured the evolution of money—not all 18 chapters, but the core progression. I asked the system to create a map showing the major transitions: from informal social credit, to commodity-based bearer assets like shells, to the gold standard, to the fiat standard after Nixon's shock, to the eurodollar-petrodollar system, and finally to the emerging question of centralized versus decentralized digital money.

What makes this valuable isn't just the visualization. It's that the system understands the argument structure of the book because my highlights are organized by chapter. It knows which chapters support which parts of the evolution. It can zoom in on specific transitions or pull back to show the whole arc.

We refined the map together. I asked it to emphasize certain turning points. It suggested connections I hadn't explicitly thought about. The final artifact goes back into my knowledge base, searchable and reusable for future conversations.

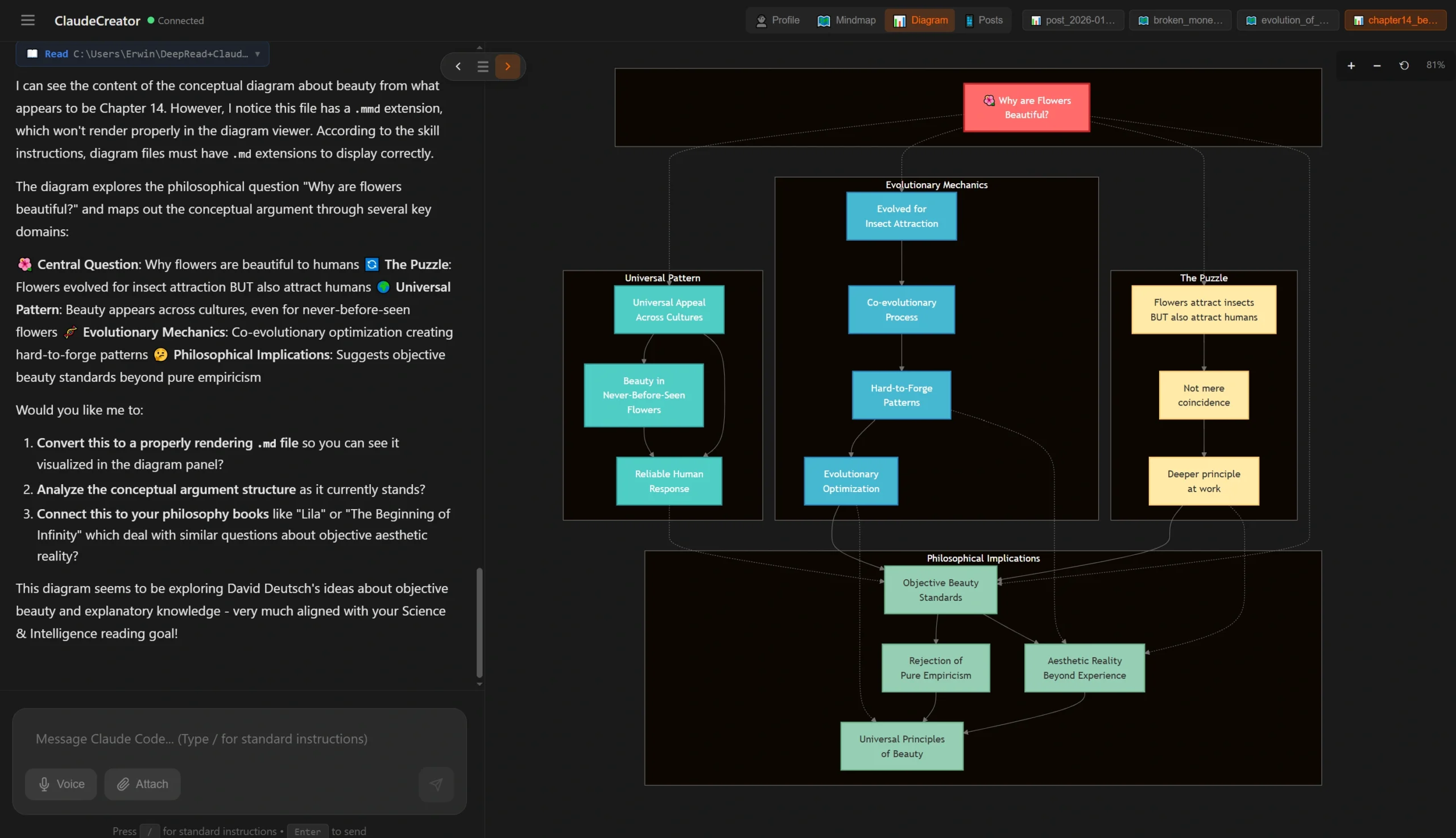

David Deutsch's The Beginning of Infinity has a chapter called "Why Are Flowers Beautiful?" It's one of those chapters where the title doesn't immediately tell you what you're in for.

Before reading it, I wanted a conceptual diagram—an overview of the argument that would prepare me for what's coming. This is exactly what Mortimer Adler calls "inspectional reading" in How to Read a Book: understanding the structure before diving into the details.

The system generated a diagram showing the chapter's logical flow. Not a summary, but a map of how the argument unfolds. This lets me read with better comprehension because I understand where we're going.

Again, this only works because the highlights preserve the book's structure. The system doesn't just know isolated quotes—it understands how ideas build on each other within chapters.

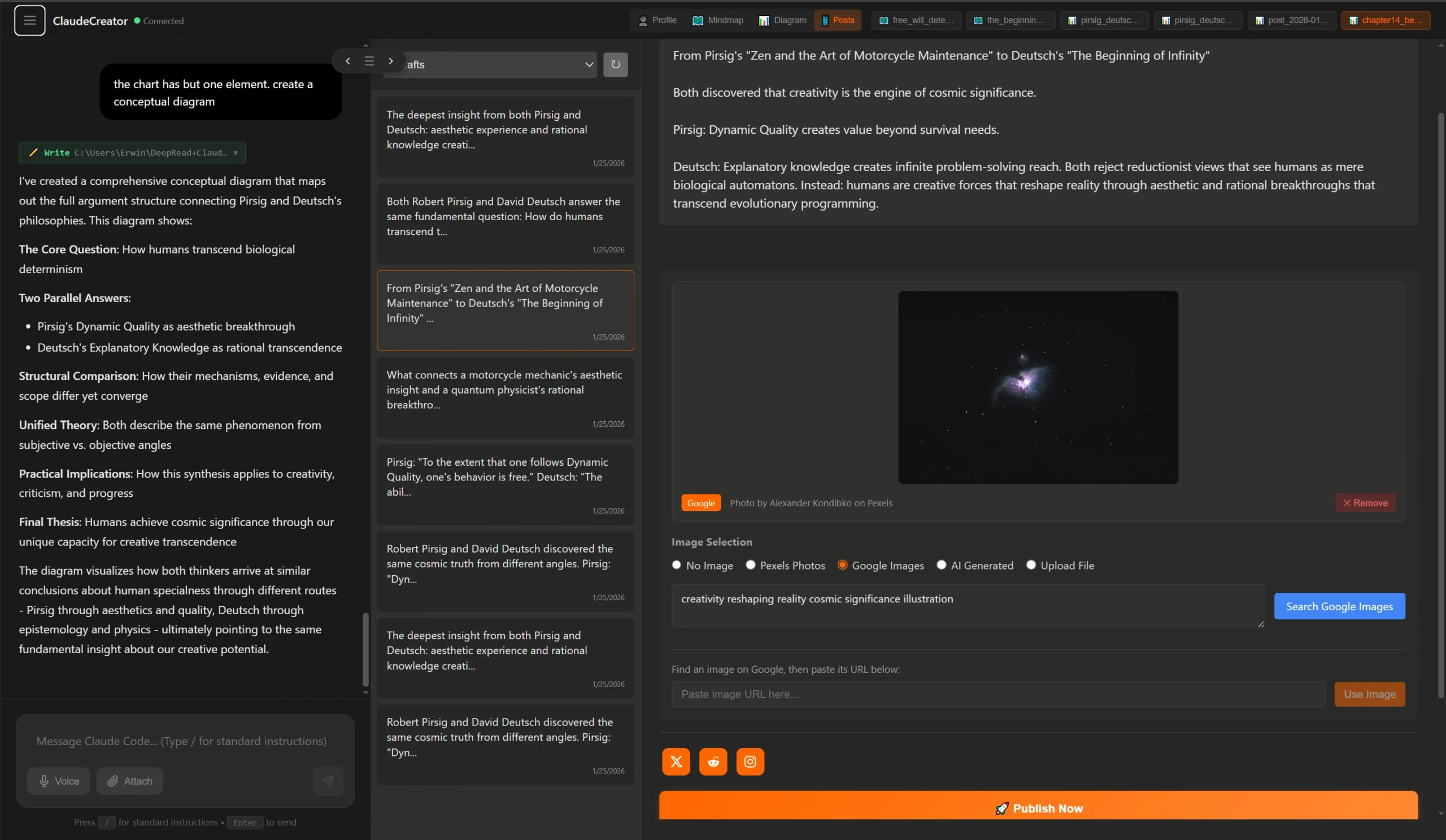

Here's where things get really interesting: asking questions that span multiple books.

I asked the system about free will and determinism. This isn't a question any single book answers definitively. It's a tension that runs through philosophy, and I've read multiple authors who address it from different angles.

The system searched across my entire library—Marcus Aurelius on Stoic determinism, Robert Pirsig's Metaphysics of Quality, David Deutsch on explanatory knowledge, Jordan Peterson on responsibility, Dostoevsky on human will. It pulled relevant passages, showed me different positions, and helped me see connections I hadn't noticed before.

What emerged was an insight about the convergence between Pirsig's "Dynamic Quality" and Deutsch's "universal reach of explanations"—both pointing to human creativity as the source of what we might call free will.

From this discussion, we created a post documenting the insight:

From Pirsig's "Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance" to Deutsch's "The Beginning of Infinity"—both discovered that creativity is the engine of cosmic significance.

Pirsig: Dynamic Quality creates value beyond survival needs.

Deutsch: Explanatory knowledge creates infinite problem-solving reach.

Both reject reductionist views that see humans as mere biological automatons. Instead: humans are creative forces that reshape reality through aesthetic and rational breakthroughs that transcend evolutionary programming.

The post goes back into the system, tagged and searchable. The next time I'm thinking about creativity, free will, or human agency, this synthesis will be part of what the system can draw on.

I've done similar cross-book explorations on power and politics, drawing on Orwell's 1984, Mises on the ideological foundations of power, Lyn Alden on the petrodollar system. When recent moves by the US administration raise questions, my books provide context that goes deeper than news cycles.

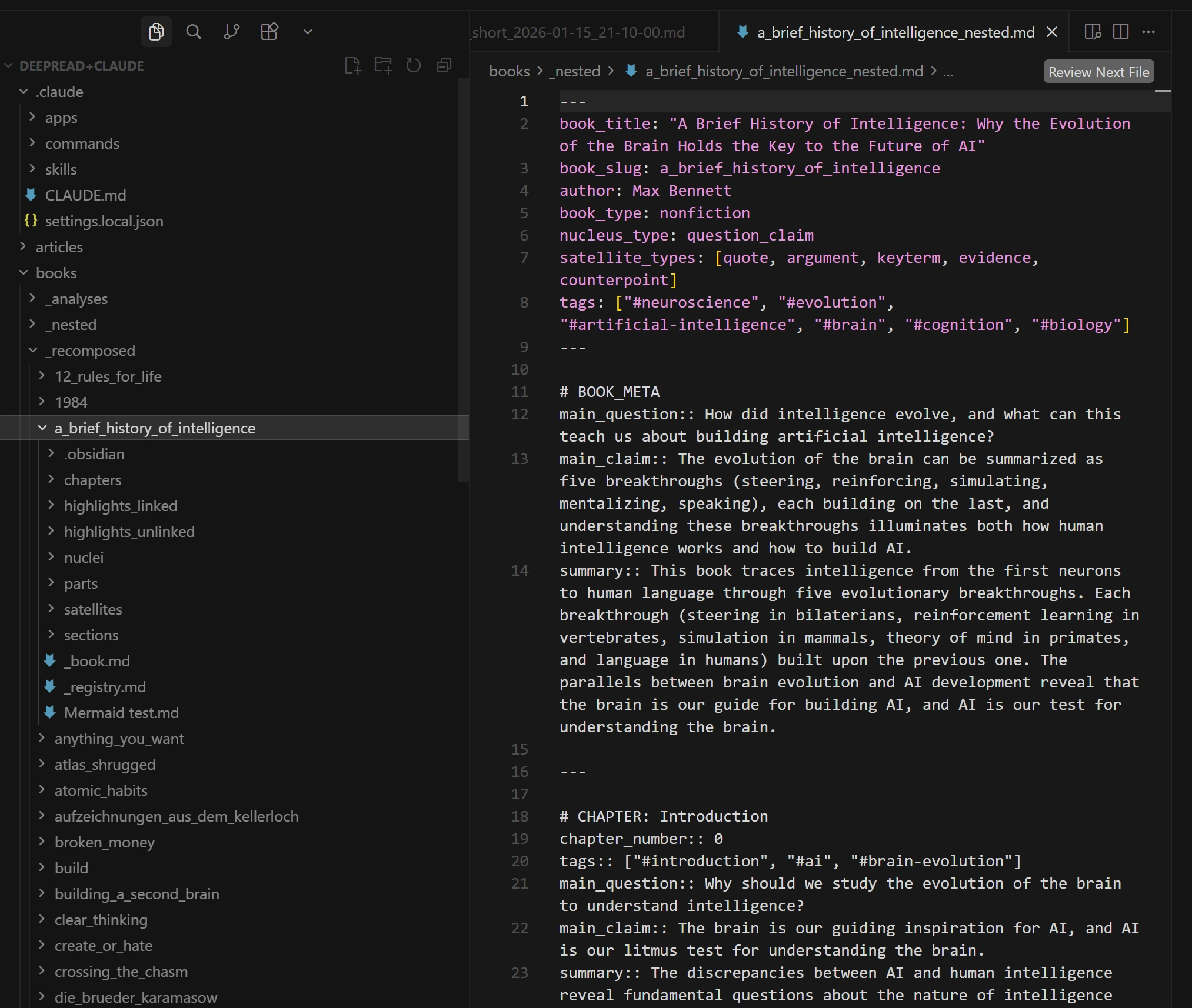

The technical foundation is straightforward but crucial: my highlights are exported from DeepRead into markdown files, structured by chapters and nested hierarchically. Each book preserves its argument structure—the nucleus-satellite model I detailed in my article on Claude Code + Kindle Highlights.

This structure is what enables intelligent retrieval. As I explained in A Book's Chapter Structure as a Tool for Understanding and Learning, chapters aren't arbitrary divisions—they're units of argument. When highlights preserve this structure, the AI can understand not just what ideas appear in a book, but how they relate to each other.

The system uses semantic search, not keyword matching. It finds what's actually relevant to my question, not just what contains the same words. And because it has access to complete books through Claude Code's file system, it can work across my entire library at once.

But here's what makes it genuinely useful: the learning loop.

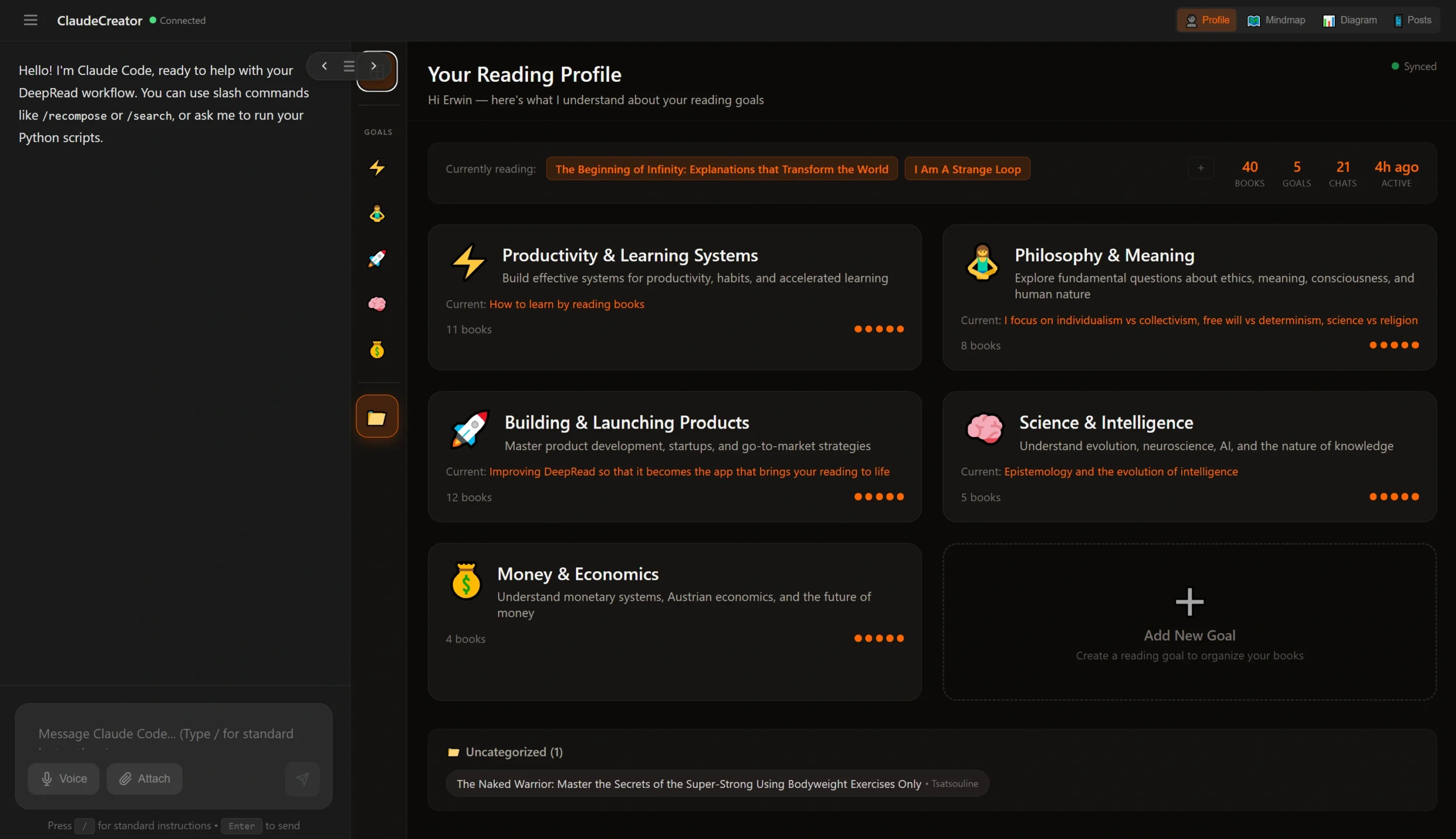

The system builds a reading profile based on my books and highlights. It clusters them into reading goals automatically—philosophy, economics, learning theory, whatever patterns emerge. I refine this, adding detail about my current projects and the questions I'm wrestling with.

Every conversation updates the profile. Every artifact we create—mind maps, diagrams, posts—gets logged and indexed. The system learns not just what I've read, but what I'm interested in, what I'm working on, what kinds of connections I find valuable.

Over time, it gets better at knowing when to surface a particular insight. It suggests next actions based on what we've been discussing. It reminds me of things I've explored before when they become relevant again.

This is why I call it bringing reading to life. The knowledge doesn't just sit there. It grows, connects, and actively participates in my thinking.

I'm experimenting with different retrieval mechanisms—testing alternatives to see what works best for different kinds of queries. The goal is a system that not only responds intelligently but proactively suggests what I should work on next.

I'm exploring a daily dashboard of next best actions: "Based on your recent reading and current projects, here are three things you could explore today." Proactive suggestions, not just reactive responses.

I'm also working on Telegram integration for quick notes on the go. Send a message to the system, and it gets refined and incorporated into future queries. The system becomes something I can interact with anytime, anywhere.

But here's what excites me most: building this together.

I'm bringing these capabilities to DeepRead's next phase, and I want to do it through co-creation with people who are serious about making their reading matter. If you're experimenting with your own systems, if you have ideas about what would make this more powerful, if you want to push the boundaries of what's possible—I want to hear from you.

Contact me with your questions, your setups, your ideas. It's greatly appreciated when people share what they're building. We can learn from each other and make these systems better together.

And if you want to try this approach yourself, the AI features are available through DeepRead.

This is just the beginning. The vision is a system that truly knows your reading, understands your goals, and actively helps you apply what you've learned. A curator, not a librarian. A thinking partner, not a database.

That's what it means to bring reading to life.

Ready to shape the future of DeepRead? Join the co-development community.

What you get:

Your committment: